Research Article: 2018 Vol: 22 Issue: 2

Dynamic Capabilities Theory: Pinning Down a Shifting Concept

Abbas Bleady, Qassim University

Abdel Hafiez Ali, Qassim University

Siddig Balal Ibrahim, Sudan University of Science and Technology

Keywords

Dynamic Capabilities, Dynamic Capabilities Definition, Systematic Review, Formal Concept Analysis.

Introduction

Dynamic capabilities (DC) theory emerged as both an extension to and a reaction against the inability of the resource-based view (RBV) to interpret the development and redevelopment of resources and capabilities to address rapidly changing environments. DC may be considered as a source of competitive advantage (Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997). DC theory goes beyond the idea that sustainable competitive advantage is based on a firm’s acquisition of valuable, rare, inimitable and non-substitutable (VRIN) resources. Dynamic capabilities are responsible for enabling organizations to integrate, marshal and reconfigure their resources and capabilities to adapt to rapidly changing environments. Thus, DCs are processes that enable an organization to reconfigure its strategy and resources to achieve sustainable competitive advantages and superior performance in rapidly changing environments. Despite the wealth of studies discussing the idea of DC, to advance the theory further requires a collective effort on the part of researchers both to illustrate concepts related to the theory and how to link them with empirical practices within organizations.

With that last statement in mind, the current paper aims to investigate two fundamental questions: first, whether there is a commonly agreed-upon empirically based definition of DC; and second, which are the most influential conceptual definitions that have affected previous empirical research in the field of DC over the period 1997 to 2015. The starting year was chosen because it saw the publication of Teece, Pisano & Shuen’s paper (1997), which is considered a key reference in the field of business economics and has generated major debate among researchers in the business strategy field when presenting their conceptual definition of DC. The paper is structured as follows: the first section provides the introduction; the second section sets out the theoretical background and a literature review; the third section discusses the methodology used, while the fourth describes the data analysis; the fifth section presents the findings of our study and the sixth section presents conclusion and limitations of the study.

Dcs: Theoretical Background And Literature Survey

Dynamic capabilities (DC) theory appeared as an alternative approach to solve some of the weaknesses of RBV theory (Galvin, Rice & Liao, 2014). DC theory presents path-dependent processes that allow firms to adapt to rapidly changing environments by building, integrating and reconfiguring their resource and capabilities portfolio (Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997). However, until the 1980s there had been little interest in the subject of strategic management. Particularly in the 1980s, Porter's industry-based theory (Porter, 1979, 1980 and 1985) attracted the greatest attention (Barney & Ouchi, 1986). During that period, the RBV theory was the major subject of discussion. It viewed a firm as a portfolio of tangible and intangible resources and human resources and capabilities: the ability to combine resources in an innovative and efficient manner constituted “the firm's capabilities” (Wernerfelt, 1984, Grant, 1991; Helfat et al., 2007; Barney, 1991). In this view, competitive advantage is: “when a firm is implementing a value creating strategy not simultaneously being implemented by any current or potential competitors" (Barney, 1991, p. 102) and sustainable competitive advantage is: “when a firm is implementing a value creating strategy not simultaneously being implemented by any current or potential competitors and when these other firms are unable to duplicate the benefits of this strategy” (Barney, 1991, p. 102). These ideas emerged from VRIN resources (Barney, 1991; Tondolo & Bitencourt, 2014).

DC theory was derived from RBV theory and compensated for that theory’s shortcomings when it came to explaining sustainable competitive advantage and superior performance in a dynamic environment. Teece, Pisano & Shuen (1997) defined DCs as “the firm’s ability to integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments” (p. 516). DCs are thus “the organizational and strategic routines by which firms achieve new resource configurations as markets emerge, collide, split, evolve and die” (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000, p. 1107). Teece (2007) made a major contribution to DC theory by writing about the micro-foundations for each of the three following dimensions: sensing (identification and assessment of an opportunity), seizing (mobilization of resources to address an opportunity and to capture value) and transforming (continued renewal “reconfiguring the business firm’s intangible and tangible assets”). Nevertheless, intense criticisms have been levelled against the theory, such as the nature of the term itself and difficulties in determining the merits of the outcomes of the theory (Zahra, Sapienza & Davidson, 2006), difficulty in understanding the nature of DCs and the absence of clear models to measure these capabilities and how they affect the performance of organizations (Zott, 2003). The theory has also been criticized for being repetitive (Zollo & Winter, 2002) and ineffective in providing a complete answer regarding DCs and they operate (Schreyögg & Kliesch-Eberl, 2007). DC theory has also suffered from a lack of clarity about what constitutes its core concepts (Ambrosini & Bowman, 2009). Despite the intense growth of studies discussing the idea of DCs (Ambrosini & Bowman, 2009), the progress of the theory still requires further collective efforts from researchers to illustrate concepts related to the theory and how to link them to empirical practices within organizations (Wang & Ahmed, 2007).

Research Methodology

To achieve a systematic approach, the present research was designed in accordance with the series of steps suggested by Giudici (2009) and Newbert (2007) to build our own database in our systematic review of studies and research into dynamic capabilities at the empirical level. Our research procedure followed the steps described hereafter.

First, research and planning about databases: at this level, the authors suggested a protocol to carry out the search in databases with the stipulation that the articles selected for the search should fulfil the following requirements:

1. Have been published in scientific journals.

2. Have been published during the period 1997 to 2015 so as to cover appropriate articles in the field of dynamic capabilities at the empirical level.

3. Have been published in English.

4. Have complete texts available online for academicians and researchers at the author’s universities.

Second, determining which databases to search: at this level, the present study specified the databases in the business field which could be used by the academicians and researchers on the author’s universities websites. The databases shown in Table 1 below were selected.

| Table 1: Selected Database Title |

|

| No. | |

| 1 | Business Source Complete (Ebsco) |

| 2 | PQ Central (ProQuest) |

| 3 | Scopus |

| 4 | Wiley Online Library |

Third, searching within databases.

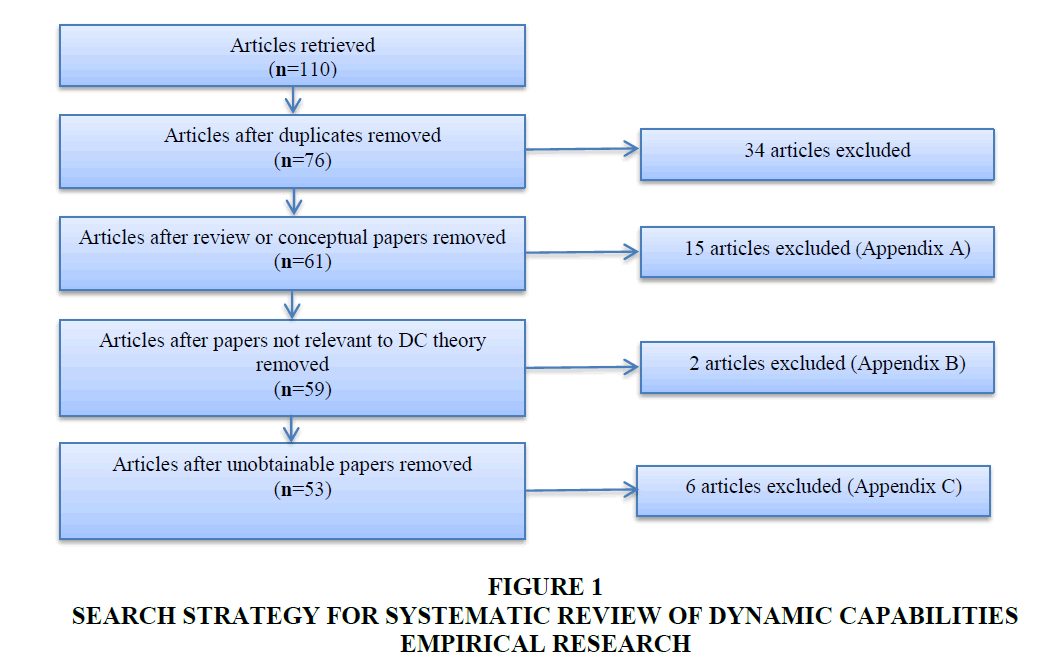

Fourth, filtering the articles retrieved and determining precisely the sample size: At this stage, a thorough and deep read of the abstracts of all the 110 articles cited from the previous stage was conducted. The main aim was to exclude repeated and contradictory articles available in the four databases and also to exclude articles that do not have any relevance for the present study despite meeting the protocol requirements. As a result of this screening and filtering process, we determined that the total specific sample size was to be 53 articles. They were all retrieved from high-quality journals represented in the databases searched, as shown in Figure 1 and Table 2.

| Table 2: Selected Journals And Number Of Articles Retrieved |

||

| Journals | Abbreviation | No. of Articles Considered |

|---|---|---|

| African Journal of Business Management | AJBM | 3 |

| Baltic Journal of Management | BJM | 1 |

| British Journal of Management | BJM | 2 |

| Corporate Governance | CORG | 2 |

| Indian Journal of Science and Technology | IJST | 1 |

| Industrial Management & Data Systems | IMDS | 1 |

| International Small Business Journal | ISBJ | 1 |

| Information & Management | IM | 1 |

| Innovation: Management, Policy & Practice | IMPP | 1 |

| International Journal of Business Excellence | IJBE | 1 |

| International Journal of Electronic Business Management | IJEBM | 1 |

| International Journal of Manpower | IJM | 1 |

| International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management | IJPPM | 1 |

| International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management | IJRDM | 1 |

| International Marketing Review | IMR | 1 |

| International Small Business Journal | ISBJ | 1 |

| Journal of Product Innovation Management | JPIM | 1 |

| Journal of the Association for Information Systems | JAIS | 1 |

| Journal of Business Research | JBR | 3 |

| Journal of CENTRUM Cathedra | JCC | 1 |

| Journal of Convergence Information Technology | JCIT | 1 |

| Journal of East European Management Studies | JEEMS | 1 |

| Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy | JEC | 1 |

| Journal of International Business Studies | JIBS | 1 |

| Journal of International Entrepreneurship | JIE | 1 |

| Journal of Management & Organization | JMO | 2 |

| Journal of Management Information Systems | JMIS | 1 |

| Journal of Management Studies | JMS | 1 |

| Journal of Product Innovation Management | JPIM | 1 |

| Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing | JRIM | 1 |

| Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development | JSBED | 1 |

| Journal of Small Business Management | JSBM | 1 |

| Journal of Strategy and Management | JSM | 1 |

| Journal of Systems and Information Technology | JSIT | 1 |

| Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science | JAMS | 1 |

| Knowledge and Process Management | KPM | 2 |

| Management and Production Engineering Review | MPER | 1 |

| Management Decision | MD | 4 |

| Management International Review | MIR | 2 |

| Supply Chain Management | SCM | 1 |

| Total Quality Management & Business Excellence | TQMBE | 1 |

| Total | 53 | |

Data Analysis

The sample selected for our study was 53 articles published during the target period. The study analysed all articles for the dimension the concept of DC to discover whether there was any agreement among researchers about the basic concepts of DC theory and its primary focus, see Table 3.

| Table 3: Analysis Of Target Sample Articles According To Dc Concept/Definition | |||

| Author/s | Year | DC Definition on which the Article was Based | Primary focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sher & Lee | 2004 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “an organization’s ways of responding in a rapidly changing environment,” (in the article), p. 933. | Organizational methods |

| Jantunen et al. | 2005 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “the structures and processes that constitute firm's ability to reconfigure its asset base to match the requirements of the changing environment?the firm’s ability to sense and seize opportunities,” (Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997; Eisenhardt and Martin, 2000; Winter, 2003; Teece, 2007), p. 225. | Entrepreneurial and organizational skills |

| Newbert | 2005 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “the antecedent organizational and strategic routines by which managers alter their resource base -acquire and shed resources- to generate new value-creating strategies,” (Eisenhardt and Martin, 2000), p. 57. | Organizational routines |

| Ayuso, Rodriguez & Ricart | 2006 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “the firm’s ability to integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environments,” (Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997), p. 953. | Organizational skills |

| Boccardelli & Magnusson | 2006 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “the explicit acquisition, transformation or re-combination of company resources,” (Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997; Eisenhardt and Martin, 2000), p. 170. | Organizational skills and routines |

| Menguc & Auh | 2006 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “the firm’s ability to integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments,” (Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997), p. 64. | Organizational skills |

| Benner | 2009 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “a higher-order systematic organizational practice focused on improving underlying operating routines and capabilities,” (Zollo and Winter, 2002), p. 474. | Learning patterns |

| Bruni & Verona | 2009 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “the capacity of an organization to purposefully create, extend or modify its resource base,” (Helfat et al., 2007, p. 4). p. S102. | Organizational capacity |

| Bullón | 2009 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “the capacity of an organization to purposefully create, extend or modify its resources,” (Helfat et al., 2007), p. 100. | Organizational capacity |

| Chen, Lee & Lay | 2009 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “an important interface driving the creation, evolution and recombination of other resources and can assist in renewing organizational resources and improving competitive strength,” (Teece, Pisano & Shue, 1997), p. 1289. | Organizational skills |

| Fang & Zou | 2009 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “the ability to build, integrate and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments,” (Teece, Pisano & Shue, 1997), p. 742. | Organizational skills |

| Hsu & Chen | 2009 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “organizational routines and can also be used to either enhance existing or build new resource configurations in the pursuit of competitive advantages,” (Eisenhardt and Martin, 2000). p. 587. | Organizational routines |

| Laamanen & Wallin | 2009 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “the firm’s ability to integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environments,” (Teece, Pisano & Shue, 1997), p. 953. | Organizational skills |

| Barrales-Molina, Benitez-Amado & Perez-Arostegui | 2010 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “the firm’s abilities to integrate, construct and reconfigure the internal and external competences so as to react quickly to dynamic environments,” (Teece, Pisano & Shue, 1997), p. 1356. | Organizational skills |

| Bustinza, Molina & Arias-Aranda | 2010 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “those that bring about the changes in the processes applied by the firm,” (Zahra, Sapienza & Davidsson, 2006), p. 4067. | Organizational skills |

| Chirico & Nordqvist | 2010 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “Processes designed to acquire, exchange, transform and shed internal and external resources,” (in the article), p. 499. | Entrepreneurial resource management processes |

| Hou & Chien | 2010 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “the routines in a firm that guide and facilitate the development of the firm’s organizational capabilities by changing the underlying resource base in the firm,” (Eisenhardt and Martin, 2000), p. 97. | Organizational routines |

| Cui & Jiao | 2011 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “recreate internal and external resources in response to dynamic and rapidly shifting market environments in order to attain and sustain competitive advantage,” (Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997; Winter, 2003), p. 386. | Organizational skills |

| Evers | 2011 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “adapt, integrate and re-configure internal and external organizational skills, resources and functional competencies to develop competitive advantage and respond to changing environments,” (Pierce, Boerne & Teece, 2001), p. 519. | Organizational skills |

| Jiao, Alon & Cui | 2011 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external resources and/or competencies to address their changing environments,” (Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997), p. 133. | Organizational and managerial skills |

| Lee et al. | 2011 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “problem-solving patterns and procedures of organizational KA whose main upgrading gateway is learning and stable organizational governance,” (in the article), p. 4197. | Problem solving patterns and routines |

| Lim, Stratopoulos & Wirjanto | 2011 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “the firm’s ability to integrate, build and reconfigure IT with organizational and managerial processes in order to align with a rapidly changing competitive environment,” (in the article), p. 50. | Organizational skills |

| Liu & Hsu | 2011 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “a firm’s ability to integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environments the firm’s specific and distinctive processes relating to the transformation of resource reconfiguration to cope with environmental change,” (Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997; Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000), p. 1513. | Organizational skills and routines |

| Ludwig & Pemberton | 2011 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “a set of specific and identifiable processes or a pool of [controllable] resources that firms can integrate, reconfigure, renew and transfer”, p. 218. | Organizational skills and processes |

| Wang & Shi | 2011 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “firm's ability to integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments,” (Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997), p. 203. | Organizational skills |

| Adeniran & Johnston | 2012 | The Dynamic capabilities defined as “a firm's capacity to sense, create, extend, modify, reconfigure, integrate and renew its ordinary or core capabilities to achieve and maintain competitive advantage in fast changing environments,” (Ambrosini & Bowman, 2009; Helfat et al., 2007; Wang & Ahmed, 2007; Winter, 2003), p. 4090. | Organizational capacity |

| Khalid & Larimo | 2012 | Unspecified definition for DCs, but the article has been influenced by previous research work such as Eisenhardt and Martin (2000) and Zahra, Sapienza & Davidsson (2006). | Organizational skills and routines |

| Kuuluvainen | 2012 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “the capacity to renew competencies so as to achieve congruence with the changing business environment” by “adapting, integrating and configuring internal and external organizational skills, resources and functional competencies,” (Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997), p. 384. | Organizational skills |

| Newey, Verreynne & Griffiths | 2012 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “to create, extend or modify, integrate, build, reconfigure and/or sense, seize and transform firm’s operating capabilities,” (Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997), p. 123. | Organizational and managerial skills |

| Rodenbach & Brettel | 2012 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “alter, expand and reconfigure a firm’s strategic assets,” (Eisenhardt and Martin, 2000; Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997), p. 611. | Organizational skills and routines |

| Wu & Hu | 2012 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “part of an on-going process wherein new knowledge is acquired from organizational members and integrated with existing knowledge for its further sharing and application in order to create value,” p. 981. | Organizational skills and processes |

| Yung & Lai | 2012 | Unspecified definition for DCs, but the article has been influenced by previous research work such as Teece, Pisano & Shuen (1997), Eisenhardt and Martin (2000), Zollo & Winter (2002) and Zott (2003). | Organizational skills, routines and learning patterns |

| Kokin et al. | 2013 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “an organizational trait,” (in the article), p. 67. | Organizational characteristics |

| Agarwal & Selen | 2013 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “the organizational and strategic routines by which firms achieve new resource configurations as markets emerge, collide, split, evolve and die,” (Eisenhardt and Martin, 2000), p. 523. | Organizational routines |

| Caniato, Moretto & Caridi | 2013 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “a subset of the competences/capabilities which allow the firm to create new products and processes and respond to changing market circumstances,” p. 943. | Organizational skills |

| Frasquet, Dawson & Molla | 2013 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “the firm’s ability to integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environments?is a learned and stable pattern of collective activity through which the organization systematically generates and modifies its operating routines in pursuit of improved effectiveness?the capacity of an organization to purposefully create, extend or modify its resource base,” (Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997; Zollo & Winter, 2002; Helfat et al., 2007), pp. 1511?1512. | Organizational skills, learning patterns and capacity |

| Grimaldi, Quinto & Rippa | 2013 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “the process of activating, copying, transferring, synthesizing, reconfiguring and redeploying different skills and resources,” (Eisenhardt and Martin, 2000), p. 201. | Organizational routines |

| Kindström, Kowalkowski & Sandberg | 2013 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “routines within the firm's managerial and organizational processes that aim to gain, release, integrate and reconfigure resources,” (Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997), p. 1064. | Organizational skills |

| Koskinen & Sahebi | 2013 | Dynamic capabilities defined as DCs’ “ability to integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external resources and competences in a rapidly changing business environment,” p. 63. | Organizational skills |

| Nedzinskas et al. | 2013 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “the capacity to sense and shape opportunities and threats, to seize opportunities and to maintain competitiveness through enhancing, combining, protecting and when necessary, reconfiguring the business enterprise’s intangible and tangible assets,” (Teece, 2007), p. 378. | Managerial skills |

| Singh, Oberoi & Ahuja | 2013 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “competencies that allow a firm to quickly reconfigure its organizational structure and routines in response to new opportunities,” (Fan et al., 2004), p. 1446. | Organizational skills |

| Cheng-Fei Tsai & Shih | 2013 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “firm's ability to integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments,” (Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997), p. 1018. | Organizational skills |

| Kim | 2014 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “ability to cope with the fast-changing market environment and properly change companies' sources according to the time and situation to satisfy customers' needs,” (Ambrosini and Bowman, 2009), p. 88. | Organizational skills |

| Cheng, Chen & Huang | 2014 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “to integrate or recombine important resources (such as new knowledge) that will support a firm’s performance in responding to customer needs quickly,” (Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997), p. 174. | Organizational skills |

| Gnizy, Baker & Grinstein | 2014 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “the capacity to sense and shape opportunities and threats, to seize opportunities and to maintain competitiveness through enhancing, combining, protecting and when necessary, reconfiguring the business enterprise’s intangible and tangible assets,” (Teece, 2007), p. 479. | Managerial skills |

| Ljungquist | 2014 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “the capacity of an organization to purposefully create, extend or modify its resource base,” (Helfat et al., 2007), p. 83. | Organizational capacity |

| Makkonen et al. | 2014 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “the organization's capacity to purposefully create, extend and modify the existing resource base, thus facilitate the change and renewal of current processes and promote innovation to achieve a better fit with the environment,” (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Helfat et al., 2007; Winter, 2003; Zahra et al., 2006; Zollo &Winter, 2002), p. 2708. | Organizational capacity and routines |

| Piening & Salge | 2015 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “How firms create, implement and replicate new operating routines,” (in the article), p. 94. | Organizational processes |

| Choi & Moon | 2015 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “the ability of organizational convergence activities such as sensing of convergence demands, integrating of convergence resources, coordinating of organizational competences and assets in convergence environment,” (in the article), p. 3. | Organizational and managerial skills |

| Maijanen, Jantunen & Hujala | 2015 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “the capacity to sense and shape opportunities and threats, to seize opportunities and to maintain competitiveness through enhancing, combining, protecting and, when necessary, reconfiguring the business enterprise’s intangible and tangible assets,” (Teece, 2007), p. 5. | Managerial skills |

| Simon et al. | 2015 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “the ability and processes of the firm to configure its resources and thus allow the organization to adapt and evolve,” (in the article), p. 916. | Organizational skills and processes |

| Rice et al. | 2015 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “the ability to integrate, build and reconfigure the resource base over time, in order to respond to changing environments,” (Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997), p. 232. | Organizational skills |

| Wilhelm, Schlömer & Mourer | 2015 | Dynamic capabilities defined as “a meta-routine designed to improve a company’s operating routines,” (in the article), p. 328. | Meta-routine |

Note: Based on our review of articles included in Table 3 according to the dimension of conceptual definition, the following primary focus of "dynamic capabilities" definitions can be identified: "Organizational Methods", "Entrepreneurial Skills", "Organizational Skills", "Organizational Routines", "Learning Patterns", "Organizational Capacity", " Entrepreneurial Resource Management Processes", "Problem Solving Patterns", "Managerial Skills", "Organizational Processes", "Organizational Characteristics" and "Meta-Routine". Our review did not elaborate on these key factors in detail, since they are beyond the scope of this study, which focuses only on the source of the definition of the dynamic capabilities.

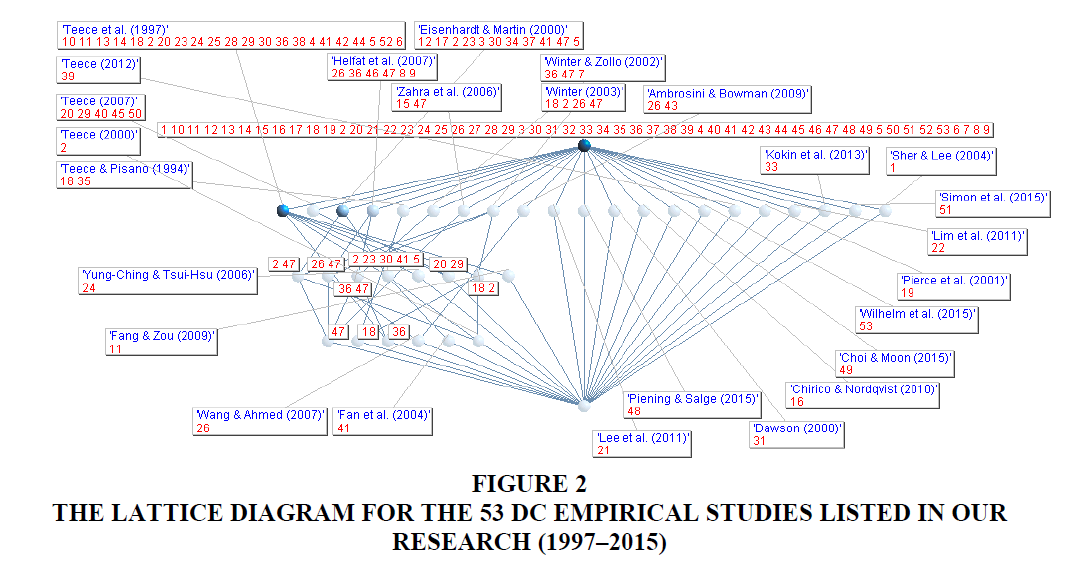

To analyse the articles listed above in the sample of the present study according to the specific dimensions of the definitions of DC they proposed or provided, we used formal concept analysis (FCA), which aims to achieve clarity of concepts by revealing observable, elementary properties of the subsumed objects and through which attributes can be modelled and predicted in a clear and concise manner (Wollbold, 2012). FCA is an applied part of lattice theory that helps in the formalization of concepts as basic units of human thinking and the analysis of data in a logical form (Ignatov, 2014). The following Figure 2 shows the lattice diagram for the 53 empirical studies of DC listed in our sample (1997-2015).

From our review of the concepts and definitions of DC in the selected sample of articles in this study, it emerged that 22 of these listed articles (constituting 41.51%) relied upon a single specific definition presented by Teece, Pisano & Shuen (1997) either as the sole, unique source of the definition the article applied or in combination with other sources to build their theoretical foundations. This finding reflects the confidence these researchers place in a theoretical framework presented by Teece, Pisano & Shuen (1997) in formulating the empirical models described in those articles. Moreover, this finding could be considered an indication that a more effective theoretical framework has been achieved to direct the trend of empirical DC studies.

In contrast, 11 articles (constituting 20.75%) relied upon another specific definition (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000) as the sole, unique source of the definition they applied or in combination with other sources. However, six further articles (constituting 11.32%) also relied upon another single specific definition created by Helfat et al. (2007), either as a sole, unique source or in combination with other sources. Of the total number of articles selected, 22.65% tended to rely upon compound definitions or adopted their own definitions to build their theoretical frameworks and they then tested them empirically based on their hypotheses and objectives. Finally, two articles (3.77%) did not include any definition of DCs at all (that of Khalid & Larimo, 2012; Yung & Lai, 2012). The present study, therefore, suggests that the majority of previous research in DCs can be classified as focusing on one or other of two “schools”; the first school builds on the theoretical basis of Teece, Pisano & Shuen (1997), whereas the second school relies on the theoretical basis of Eisenhardt and Martin (2000) (Table 4).

| Table 4: The Most Influential Conceptual Definitions Affecting Previous Empirical Research In Dynamic Capabilities | |

| Authors | Definition |

|---|---|

| Teece, Pisano & Shuen (1997, p. 516) | “The firm’s ability to integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments” |

| Eisenhardt and Martin (2000, p. 1107) | “The organizational and strategic routines by which firms achieve new resource configurations as markets emerge, collide, split, evolve and die” |

Conclusion And Limitations

We analysed all of the articles listed in our sample according to the dimensions of the definition with which they worked. From that analysis, the following conclusions can be drawn.

1. There exists a wide disparity among scholars and researchers in defining DC. Based on the 53 selected sample articles studied in this research, empirical DC studies have not been able to reach a consensus about a commonly agreed-upon empirically based definition of DC.

2. Researchers are divided into what can be considered two basic schools of thought when forming a theoretical framework for DC. The two schools are the following:

a. The first “school,” developed by Teece, Pisano & Shuen (1997), is numerically preponderant the more influential in providing the theoretical foundations for the sample articles mentioned in this present paper. This first school views DC as “the firm's ability to integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments” (p. 516).

b. The second “school,” which was developed by Eisenhardt and Martin (2000), is the second in impact on the articles analysed in the sample of the present research as regards building the theoretical foundations of DC. This second school defines DC as “the organizational and strategic routines by which firms achieve new resource configurations as markets emerge, collide, spilt, evolve and die” (p. 1107).

3. Notwithstanding the preceding item no. (2), there are alternative definitions of DC used by researchers as revealed by our research.

4. There is no unified conceptual definition of the dynamic capabilities and the primary focus of its concept remains to a large extent theoretically undefined and need more attention in future research.

Despite the importance of the research results, which can be considered a guide for empirical research in DCs, there exist some limitations of the present study. These are as follows:

1. It relied solely on searching electronic databases available to learners and researchers at our own universities. There might be other important electronic databases available to the researchers whose articles we studied containing articles not used in this study.

2. The articles were published electronically.

3. They were published in English.

4. The present research was restricted to the period 1997 to 2015.

Due to the above limitations, it may be difficult to generalize the results of this study.

Appendix

| Appendix A: Articles Excluded Because Of Their Type As A Review Or Conceptual Paper |

|

| No. | Author/s and Year |

|---|---|

| 1 | Arifin (2015) |

| 2 | Arndt & Bach (2015) |

| 3 | Arndt & Jucevicius (2013) |

| 4 | Beske (2012) |

| 5 | Cavusgil, Seggie & Talay (2007) |

| 6 | Clifford Defee & Fugate (2010) |

| 7 | Eriksson (2013) |

| 8 | Eriksson (2014) |

| 9 | Fearon et al. (2013) |

| 10 | Helfat & Martin (2015) |

| 11 | Hou (2008) |

| 12 | Kim, Song & Triche (2015) |

| 13 | Markova (2012) |

| 14 | Vogel & Güttel (2013) |

| 15 | Zhensen & Guijie (2013) |

| Appendix B: Articles Excluded Because They Are Not Relevant To The Dc Theory | |

| No. | Author/s and Year |

|---|---|

| 1 | Liu & Bi (2013) |

| 2 | Pugno (2015) |

| Appendix C: Articles Excluded Because Of The Need For Further Authorization Which Was Not Available To The Authors Of This Paper | |

| No. | Author/s and Year |

|---|---|

| 1 | Duh (2013) |

| 2 | Kaltenbrunner & Renzl (2014) |

| 3 | Lin, Wu & Lin (2008) |

| 4 | McGuinness & Morgan (2005) |

| 5 | Pedron & Caldeira (2011) |

| 6 | Susanti & Arief (2015) |

References

- Adeniran, T.V. & Johnston, K.A. (2012). Investigating the dynamic capabilities and competitive advantage of South African SMEs. African Journal of Business Management, 6(11), 4088-4099.

- Agarwal, R. & Selen, W. (2013). The incremental and cumulative effects ofdynamic capability building on service innovation in collaborative service organizations. Journal of Management & Organization, 19(05), 521-543.

- Ambrosini, V. & Bowman, C. (2009). What are dynamic capabilities and are they a useful construct in strategic management? International Journal of Management Reviews, 11(1), 29-49.

- Arifin, Z. (2015). The effect of dynamic capability to technology adoption and its determinant factors for improving firm's performance; toward a conceptual model. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 207, 786-796.

- Arndt, F. & Bach, N. (2015). Evolutionary and Ecological conceptualization of dynamic capabilities: Identifying elements of the Teece and Eisenhardt schools. Journal of Management & Organization, 21(05), 701-704.

- Arndt, F. & Jucevicius, G. (2013). Antecedents and outcomes of dynamic capabilities: The effect of structure. Social Sciences, 81(3), 35-42.

- Ayuso, S., Rodríguez, M. & Ricart, J. (2006). Using stakeholder dialogue as a source for new ideas: A dynamic capability underlying sustainable innovation. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 6(4), 475-490.

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99-120.

- Barney, J.B. & Ouchi, W.G. (1986). Organizational economics. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Barrales-Molina, V., Benitez-Amado, J. & Perez-Arostegui, M.N. (2010). Managerial perceptions of the competitive environment and dynamic capabilities generation. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 110(9), 1355-1384.

- Benner, M.J. (2009). Dynamic or static capabilities? Process management practices and response to technological change. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 26(5), 473-486.

- Beske, P. (2012). Dynamic capabilities and sustainable supply chain management. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 42(4), 372-387.

- Boccardelli, P. & Magnusson, M.G. (2006). Dynamic capabilities in early-phase entrepreneurship. Knowledge and Process Management, 13(3), 162-174.

- Bruni, D.S. & Verona, G. (2009). Dynamic marketing capabilities in science-based firms: An exploratory investigation of the pharmaceutical industry. British Journal of Management, 20(s1), S101-S117.

- Bullón, L.A. (2009). Competitive advantage of operational and dynamic information technology capabilities. JCC: The Business and Economics Research Journal, 2(1), 86-107.

- Bustinza, O.F., Molina, L.M. & Arias-Aranda, D. (2010). Organizational learning and performance: Relationship between the dynamic and the operational capabilities of the firm. African Journal of Business Management, 4(18), 4067.

- Caniato, F., Moretto, A. & Caridi, M. (2013). Dynamic capabilities for fashion-luxury supply chain innovation. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 41(11/12), 940-960.

- Cavusgil, E., Seggie, S.H. & Talay, M.B. (2007). Dynamic capabilities view: Foundations and research agenda. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 15(2), 159-166.

- Chen, H.H., Lee, P.Y. & Lay, T.J. (2009). Drivers of dynamic learning and dynamic competitive capabilities in international strategic alliances. Journal of Business Research, 62(12), 1289-1295.

- Cheng, J.H., Chen, M.C. & Huang, C.M. (2014). Assessing inter-organizational innovation performance through relational governance and dynamic capabilities in supply chains. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 19(2), 173-186.

- Cheng-Fei Tsai, P. & Shih, C.T. (2013). Responsible downsizing strategy as a panacea to firm performance: The role of dynamic capabilities. International Journal of Manpower, 34(8), 1015-1028.

- Chirico, F. & Nordqvist, M. (2010). Dynamic capabilities and trans-generational value creation in family firms: The role of organizational culture. International Small Business Journal, 28(5), 487-504.

- Choi, S. & Moon, T. (2015). The influence of resource competence on convergence performance through dynamic convergence capabilities. Indian Journal of Science and Technology, 8(25), 1-9.

- Clifford Defee, C. & Fugate, B.S. (2010). Changing perspective of capabilities in the dynamic supply chain era. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 21(2), 180-206.

- Cui, Y. & Jiao, H. (2011). Dynamic capabilities, strategic stakeholder alliances and sustainable competitive advantage: Evidence from China. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 11(4), 386-398.

- Duh, M. (2013). Toward more operational dynamic capabilities concept: Possible contribution of the dynamic enterprise construct. International Journal of Business and Management, 8(9), 24-33.

- Eisenhardt, K.M. & Martin, J.A. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: what are they? Strategic Management Journal, 21(10-11), 1105-1121.

- Eriksson, T. (2013). Methodological issues in dynamic capabilities research-a critical review. Baltic Journal of Management, 8(3), 306-327.

- Eriksson, T. (2014). Processes, antecedents and outcomes of dynamic capabilities. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 30(1), 65-82.

- Evers, N. (2011). International new ventures in ?low tech? sectors: A dynamic capabilities perspective. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 18(3), 502-528.

- Fan, T., Jones, N., Kumaraswamy, A., Narasimhalu, D., Phan, P. & Tschang, T. (2004). Dynamic capabilities: New sources of industrial competitiveness? In: Engineering Management Conference, 2004. Proceedings. 2004 IEEE International (2, 666-668). IEEE.

- Fang, E. & Zou, S. (2009). Antecedents and consequences of marketing dynamic capabilities in international joint ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(5), 742-761.

- Fearon, C., Yang, J., McLaughlin, H. & Duysters, G.M. (2013). Service orientation and dynamic capabilities in Chinese companies: A macro-analytical approach. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 30(4), 446-460.

- Frasquet, M., Dawson, J. & Mollá, A. (2013). Post-entry internationalisation activity of retailers. Management Decision, 51(7), 1510-1527.

- Galvin, P., Rice, J. & Liao, T.S. (2014). Applying a Darwinian model to the dynamic capabilities view: Insights and issues. Journal of Management & Organization, 20(2), 250-263.

- Giudici, A. (2009). Dynamic capabilities-what do we ?actually? know? A systematic assessment of the field and a research agenda.

- Gnizy, I., Baker,W.E. & Grinstein, A. (2014). Proactive learning culture. International Marketing Review, 31(5), 477-505.

- Grant, R.M. (1991). The resource-based theory of competitive advantage: Implications for strategy formulation. California Management Review, 33(3), 114-135.

- Grimaldi, M., Quinto, I. & Rippa, P. (2013). Enabling open innovation in small and medium enterprises: A dynamic capabilities approach. Knowledge and Process Management, 20(4), 199-210.

- Helfat, C.E. & Martin, J.A. (2015). Dynamic managerial capabilities: Review and assessment of managerial impact on strategic change. Journal of Management, 41(5), 1281-1312.

- Helfat, C.E., Finkelstein, S., Mitchell, W., Peteraf, M., Singh, H., Teece, D. & Winter, S.G. (2007). Dynamic capabilities: Understanding strategic change in organizations. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Hou, J.J. (2008). Toward a research model of market orientation and dynamic capabilities. Social Behaviour and Personality: An International Journal, 36(9), 1251-1268.

- Hou, J.J. & Chien, Y.T. (2010). The effect of market knowledge management competence on business performance: A dynamic capabilities perspective. International Journal of Electronic Business Management, 8(2), 96.

- Hsu, C.W. & Chen, H. (2009). Foreign direct investment and capability development. Management International Review, 49(5), 585-605.

- Ignatov, D.I. (2014, August). Introduction to formal concept analysis and its applications in information retrieval and related fields. In: Russian Summer School in Information Retrieval (pp. 1-102). Cham: Springer.

- Jantunen, A., Puumalainen, K., Saarenketo, S. & Kyläheiko, K. (2005). Entrepreneurial orientation, dynamic capabilities and international performance. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 3(3), 223-243.

- Jiao, H., Alon, I. & Cui, Y. (2011). Environmental dynamism, innovation and dynamic capabilities: The case of China. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 5(2), 131-144.

- Kaltenbrunner, K. & Renzl, B. (2014). Dynamic capabilities at the civil protection exercise: Eu Taranis, 2013. A Focused Issue on Building New Competences in Dynamic Environments (Research in Competence-Based Management, 7, 247-267) Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Khalid, S. & Larimo, J. (2012). Firm specific advantage in developed markets dynamic capability perspective. Management International Review, 52(2), 233-250.

- Kim, H. (2014). The role of WOM and dynamic capability in B2B transactions. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 8(2), 84-101.

- Kim, M., Song, J. & Triche, J. (2015). Toward an integrated framework for innovation in service: A resource-based view and dynamic capabilities approach. Information Systems Frontiers, 17(3), 533-546.

- Kindström, D., Kowalkowski, C. & Sandberg, E. (2013). Enabling service innovation: A dynamic capabilities approach. Journal of Business Research, 66(8), 1063-1073.

- Kokin, S., Pedyash, D., Alexey, V.B., Wang, T. & Shi, C. (2013). The contribution of business intelligence use and business intelligence system infrastructure flexibility to organizational dynamic capability. Journal of Convergence Information Technology, 8(6), 67-73.

- Koskinen, J. & Sahebi, D. (2013). Customer needs linked to production strategy and Firm?s dynamic capabilities. Management and Production Engineering Review, 4(2), 63-69.

- Kuuluvainen, A. (2012). How to concretize dynamic capabilities? Theory and examples. Journal of Strategy and Management, 5(4), 381-392.

- Laamanen, T. & Wallin, J. (2009).Cognitive dynamics of capability development paths. Journal of Management Studies, 46(6), 950-981.

- Lee, P.Y., Lin, H.T., Kim, H.J. & Shyr, Y.H. (2011). Knowledge articulation and dynamic capabilities in firm collaborations: An empirical comparison of Taiwanese and South Korean Enterprises. African Journal of Business Management, 5(11), 4196-4208.

- Lim, J.H., Stratopoulos, T.C. & Wirjanto, T.S. (2011). Path dependence of dynamic information technology capability: An empirical investigation. Journal of Management Information Systems, 28(3), 45-84.

- Lin, L.Y., Wu, S.H. & Lin, B. (2008). An empirical study of dynamic capabilities measurement on R&D department. International Journal of Innovation and Learning, 5(3), 217-240.

- Liu, H.Y. & Hsu, C.W. (2011). Antecedents and consequences of corporate diversification: A dynamic capabilities perspective. Management Decision, 49(9), 1510-1534.

- Liu, W. & Bi, K. (2013). Dynamic comprehensive evaluation of knowledge innovation capability of enterprises. Journal of Applied Sciences, 13(8), 1392.

- Ljungquist, U. (2014). Unbalanced dynamic capabilities as obstacles of organisational efficiency: Implementation issues in innovative technology adoption. Innovation, 16(1), 82-95.

- Ludwig, G. & Pemberton, J. (2011). A managerial perspective of dynamic capabilities in emerging markets: The case of the Russian steel industry. Journal for East European Management Studies, 16(3), 215-236.

- Maijanen, P., Jantunen, A. & Hujala, M. (2015). Dominant logic and dynamic capabilities in strategic renewal - Case of public broadcasting. International Journal of Business Excellence, 8(1), 1-19.

- Makkonen, H., Pohjola, M., Olkkonen, R. & Koponen, A. (2014). Dynamic capabilities and firm performance in a financial crisis. Journal of Business Research, 67(1), 2707-2719.

- Markova, G. (2012). Building dynamic capabilities: the case of HRIS. Management Research: Journal of the Ibero-American Academy of Management, 10(2), 81-98.

- McGuinness, T. & Morgan, R.E. (2005). The effect of market and learning orientation on strategy dynamics: The contributing effect of organisational change capability. European Journal of Marketing, 39(11/12), 1306-1326.

- Menguc, B. & Auh, S. (2006). Creating a firm-level dynamic capability through capitalizing on market orientation and innovativeness. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34(1), 63-73.

- Nedzinskas, ?., Pundziene, A., Buo?iute-Rafanaviciene, S. & Pilkiene, M. (2013). The impact of dynamic capabilities on SME performance in a volatile environment as moderated by organizational inertia. Baltic Journal of Management, 8(4), 376-396.

- Newbert, S.L. (2005). New firm formation: A dynamic capability perspective. Journal of Small Business Management, 43(1), 55-77.

- Newbert, S.L. (2007). Empirical research on the resource-based view of the firm: An assessment and suggestions for future research. Strategic Management Journal, 28(2), 121-146.

- Newey, L.R., Verreynne, M.L. & Griffiths, A. (2012). The relationship between dynamic and operating capabilities as a stage-gate process: Insights from radical innovation. Journal of Management & Organization, 18(01), 123-140.

- Pedron, C.D. & Caldeira, M. (2011). Customer relationship management adoption: using a dynamic capabilities approach. International Journal of Internet Marketing and Advertising, 6(3), 265-281.

- Piening, E.P. & Salge, T.O. (2015). Understanding the antecedents, contingencies and performance implications of process innovation: A dynamic capabilities perspective. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 32(1), 80-97.

- Pierce, J.L., Boerner, C.S. and Teece, D.J. (2001). Dynamic capabilities, competence and the behavioural theory of the firm in the economics of change. In: Augier, M. and March, J. (Eds), Choice and Structure: Essays in the Memory of Richard M. Cyert, Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham.

- Porter, M.E. (1979). How competitive forces shape strategy. Harvard Business Review, March-April, 137-145.

- Porter, M.E. (1980). Competitive strategy: Techniques for analysing industries and competitors. New York: Free Press.

- Porter, M.E. (1985). Competitive advantage. New York: Free Press.

- Pugno, M. (2015). Capability and happiness: A suggested integration from a dynamic perspective. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(6), 1383-1399.

- Rice, J., Liao, T.S., Galvin, P. & Martin, N. (2015). A configuration-based approach to integrating dynamic capabilities and market transformation in small and medium-sized enterprises to achieve firm performance. International Small Business Journal, 33(3), 231-253

- Rodenbach, M. & Brettel, M. (2012). CEO experience as micro-level origin of dynamic capabilities. Management Decision, 50(4), 611-634.

- Schreyögg, G. & Kliesch-Eberl, M. (2007). How dynamic can organizational capabilities be? Towards a dual-process model of capability dynamization. Strategic Management Journal, 28(9), 913-933.

- Sher, P.J. & Lee, V.C. 2004. Information technology as a facilitator for enhancing dynamic capabilities through knowledge management. Information & Management, 41(8), 933-945.

- Simon, A., Bartle, C., Stockport, G., Smith, B., Klobas, J.E. & Sohal, A. (2015). Business leaders? views on the importance of strategic and dynamic capabilities for successful financial and non-financial business performance. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 64(7), 908-931.

- Singh, D., Oberoi, J. & Ahuja, I. (2013). An empirical investigation of dynamic capabilities in managing strategic flexibility in manufacturing organizations. Management Decision, 51(7), 1442-1461.

- Susanti, A.A. & Arief, M. (2015). The effect of dynamic capability for the formation of competitive advantage to achieve firm?s performance (Empirical study on Indonesian credit co-operatives). Advanced Science Letters, 21(4), 809-813.

- Teece, D.J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and micro foundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28(13), 1319-1350.

- Teece, D.J., Pisano, G. & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7): 509-533.

- Tondolo, V.A.G. & Bitencourt, C.C. (2014). Understanding dynamic capabilities from its antecedents, processes and outcomes. Brazilian Business Review, 11(5), 122-144.

- Vogel, R. & Güttel, W.H. (2013). The dynamic capability view in strategic management: A bibliometric review. International Journal of Management Reviews, 15(4), 426-446.

- Wang, C.L. & Ahmed, P.K. (2007). Dynamic capabilities: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 9(1), 31-51.

- Wang, Y. & Shi, X. (2011). Thrive, not just survive: Enhance dynamic capabilities of SMEs through IS competence. Journal of Systems and Information Technology, 13(2), 200-222.

- Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 171-180.

- Wilhelm, H., Schlömer, M. & Maurer, I. (2015). How dynamic capabilitiesaffect the effectiveness and efficiency of operating routines under high and low levels of environmental dynamism. British Journal of Management, 26(2), 327-345.

- Winter, S.G. (2003). Understanding dynamic capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 24(10), 991-995.

- Wollbold, J. (2012). Attribute exploration of gene regulatory processes. arXiv preprint arXiv, 1-115.

- Wu, L. & Hu, Y.P. (2012). Examining knowledge management enabled performance for hospital professionals: A dynamic capability view and the mediating role of process capability. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 13(12), 976-999.

- Yung, I.S. & Lai, M.H. (2012). Dynamic capabilities in new product development: The case of Asus in motherboard production. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 23(9-10), 1125-1134.

- Zahra, S.A., Sapienza, H.J. & Davidsson, P. (2006). Entrepreneurship and dynamic capabilities: A review, model and research agenda. Journal of Management Studies, 43(4), 917-955.

- Zhensen, Z. & Guijie, Q. (2013). Analysing the impact of IT innovation on the development of dynamic capabilities. Journal of Convergence Information Technology, 8(9), 938-945.

- Zollo, M. & Winter, S.G. (2002). Deliberate learning and the evolution of dynamic capabilities. Organization Science, 13(3), 339-351.

- Zott, C. (2003). Dynamic capabilities and the emergence of intra-industry differential firm performance: Insights from a simulation study. Strategic Management Journal, 24(2), 97-125.